Among the many economists I have deep respect and reverence for are the classical economists like Adam Smith, David Hume, David Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill. Among the neoclassicals are William Stanley Jevons, Leon Walras, Carl Menger, Alfred Marshall, Vilfredo Pareto, Francis Edgeworth, and Lionel Robbins.

Among the many economists I have deep respect and reverence for are the classical economists like Adam Smith, David Hume, David Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill. Among the neoclassicals are William Stanley Jevons, Leon Walras, Carl Menger, Alfred Marshall, Vilfredo Pareto, Francis Edgeworth, and Lionel Robbins.

Jevons, Walras, and Menger were the founding figures of the marginalist revolution that established neoclassical economics, with Jevons and Walras independently developing the theory of marginal utility in the 1870s.

Alfred Marshall synthesized classical and neoclassical ideas in his influential textbook Principles of Economics. Pareto, a successor to Walras in Lausanne, Switzerland advanced the field, especially in general equilibrium theory. Edgeworth developed a mathematical economic theory based on utility maximization, and later economists like John Hicks and George Stigler helped broaden the scope of neoclassical thought.

My economics training was entirely restricted to neoclassical economics, or what Peter Boettke terms “mainstream economics.” That is a bit different from “mainline economics,” the economics that has been at the core of economics since Smith, et al. It is only after I had completed my formal education that I came across what is known as the “Austrian School.” It is so-called because that tradition was started by Austrians in Vienna. It began with Carl Menger, and continued with Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich August von Hayek, and others.

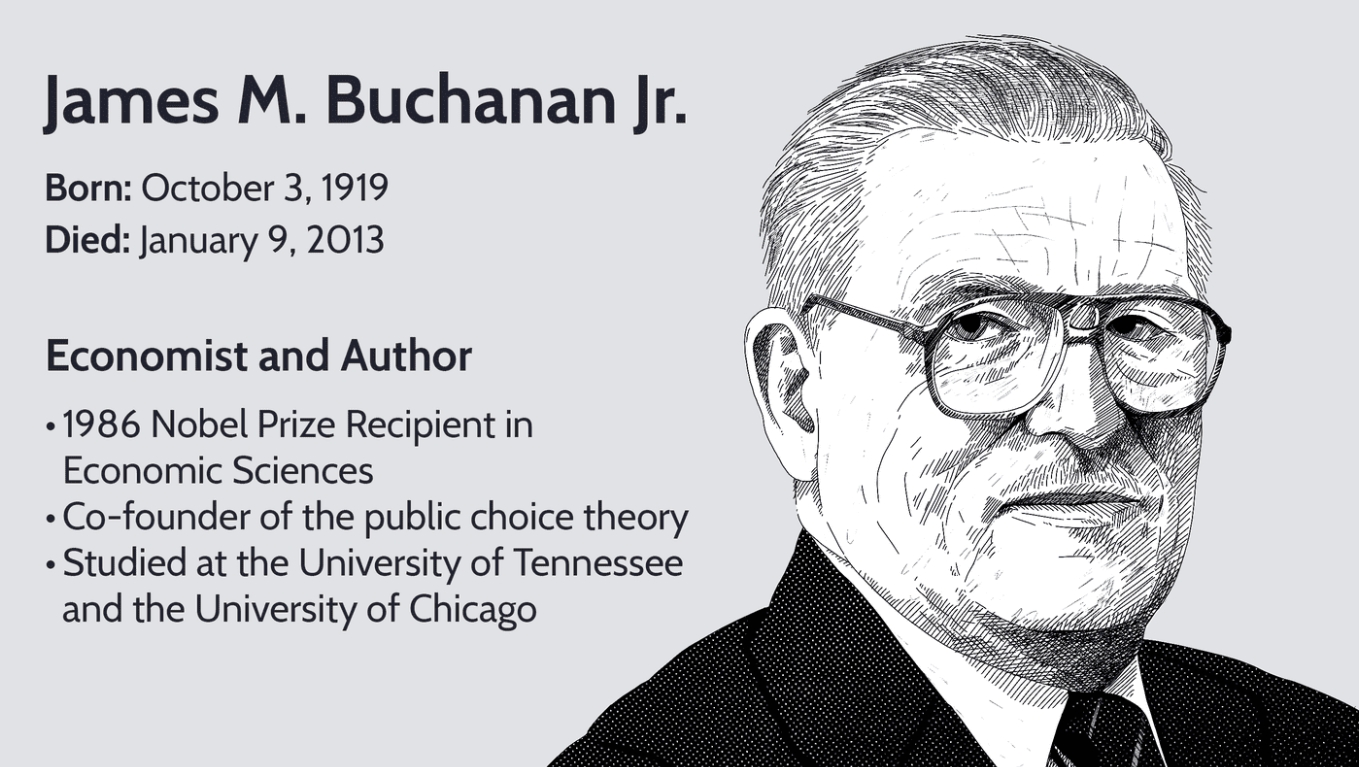

Some of the great advances in economic thought in the second half of the 20th century I came to know after completing my PhD. I mention just four: Mises, Hayek, Milton Friedman, and George Stigler. I am saving my most favorite economist for the last: James McGill Buchanan.

(Fun fact: A fellow named James Buchanan (1791 – 1868) was the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861, a period immediately preceding the American Civil War. Scholars rate him as the worst president of the US. But that’s only true if you ignore Obama, Biden and Trump.)

If I had to choose one economist among all the greats I mentioned I could spend some time with, it would be Buchanan. There are a host of reasons why. His life story is fascinating. He was born in 1913 in Tennessee to a family of limited financial means though of high social status (his grandfather was briefly the governor of Tennessee.) Remember that the south had lost the American civil war just 48 years before his birth. Being a southerner affected his outlook on freedom and government.

In his childhood, he worked on the family farm where work was done either manually or with mules and horses. He described his life on the farm as “genteel poverty” with neither indoor plumbing nor electricity.

Buchanan served in the US navy for some time and after an honorable discharge, began his graduate studies in 1945 at the University of Chicago He was essentially socialist until he enrolled in a course taught by Frank Knight. Knight also taught leading economic thinkers such as Milton Friedman and George Stigler at the University of Chicago. Within six weeks of starting his studies, Buchanan was “converted into a zealous advocate of the market order.”

Buchanan described himself to be “constitutional contractarian”, which is how I see myself. The constitution establishes a contract between and among the people.

About the Austrian School, Buchanan said, “I certainly have a great deal of affinity with Austrian economics and I have no objections to being called an Austrian. Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises might consider me an Austrian but surely some of the others would not.” He did not consider himself to be part of the Chicago School either. He was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1986.

Buchanan was seriously intelligent. That was matched with his fanatical devotion to working as hard as he could. He worked seven days a week, come rain or shine, from 7 am to 7 pm, thinking and writing economics. He explained his work ethic as “gains from specialization”—the harder he worked, the more productive he became.

I like listening to Buchanan talk. His southern accent is my most favorite of all English language accents. It’s a pleasure to listen to him, which I can do anytime, thanks to the magic of Youtube.

Alright, so what’s so special about Buchanan? I learnt from him the importance of rules, of constitutions, of the need for unanimity in framing constitutional rules, the importance of trade. Economics is the study of humans engaging in trade, not just at the marketplace of goods and services but also in the political sphere.

Economics is not just simply about supply and demand, and allocative efficiency but about the gains from trade. He believed that a first course in economics should start with the Edgeworth box diagram illustrating a 2-goods, 2-person trade. I love that idea.

Alright, this has gone on long enough. Time to learn a bit about Buchanan’s great contribution to economic thought: public choice theory. I prompted Gemini to give me a summary. Here it is:

The Political Economy of James Buchanan: Beyond the Benevolent Despot

For decades, a central function of the economist has been to advise the state, offering “optimal” policies to correct market failures and guide national progress. This tradition, however, rests on a powerful, often unexamined assumption: that the state is a “benevolent despot,” a wise and selfless entity whose only goal is to implement the public good. It was this foundational myth that Nobel laureate James Buchanan sought to dismantle. Through the lens of Public Choice theory, Buchanan argued that economists had fundamentally misunderstood the nature of politics. He contended that political actors are not selfless, and therefore the economist’s role is not to advise on policy, but to help design the constitutional “rules of the game” that constrain self-interest and protect true economic efficiency.

Buchanan’s most pointed critique is captured in his famous injunction that “Economists should, once and for all, cease and desist proffering advice to nonexistent benevolent despots.” This assertion forms the bedrock of Public Choice theory, which applies the basic tools of economics to the political arena. Instead of assuming politicians, bureaucrats, and voters are civic-minded angels, it assumes they are self-interested actors, much like consumers and firms in the marketplace. Politicians seek re-election and power; bureaucrats seek to maximize their budgets and influence; and voters often remain “rationally ignorant,” as the cost of becoming fully informed on an issue far exceeds the benefit of their single vote. This framework reveals that “government failure” is just as real and predictable as market failure, as political incentives often lead to predictably suboptimal outcomes.

Given this reality, Buchanan turned to the work of Swedish economist Knut Wicksell to redefine efficiency in the public sector. In a market, an exchange is efficient precisely because it is voluntary—both parties must agree, guaranteeing mutual benefit. Wicksell argued that to achieve this same standard of efficiency in public choice, decisions must be governed by a “rule of unanimity.” Standard majority rule, by contrast, fails this test. A 51% majority can easily impose its will on the 49%, forcing them to pay for projects they do not want, creating a net loss in social value. This is not voluntary exchange; it is coercion, and it cannot be considered efficient in the strict, Wicksellian sense.

When self-interested actors operate within a system of mere majority rule, the political process is inevitably captured by “rent-seeking.” Rent-seeking is the socially wasteful process of expending resources to secure special political favors—such as subsidies, tariffs, or monopoly licenses—rather than creating new wealth. This phenomenon is driven by an incentive flaw known as “concentrated benefits and diffuse costs.” A small special interest group will lobby fiercely for a policy that provides them with a large, concentrated benefit (e.g., a sugar tariff). The costs of this policy are spread so thinly across millions of rationally ignorant taxpayers that no one has a strong incentive to organize and fight it. The result is a system that rewards political connections over productive innovation, leading to chronic deficits and policies that shrink the economic pie for the sake of redistributing its slices.

Faced with this grim diagnosis, Buchanan argued that economists must fundamentally shift their focus. “If we seek reform in economic policy,” he wrote, “we should change the rules under which political agents or representatives act.” This is the core of “constitutional political economy.” Rather than tweaking specific tax rates or subsidy levels—a task rendered futile by the distortions of rent-seeking—the economist’s proper role is to analyze and propose changes to the constitution itself. These “rules of the game,” such as balanced-budget amendments, supermajority requirements for tax increases, or line-item vetoes, are designed to limit the state’s ability to be exploited for private gain. By making it more difficult to form coercive majorities, such rules help align the self-interest of political actors with the broader public good, forcing a closer approximation of the Wicksellian ideal of unanimous consent.

Next up: What is Public Choice Theory? (A Simple Guide)