Trade

Trade

Trade has been a defining feature of human life since time immemorial. With the possible exception of hermits, we all need to trade to survive. We consume an immense variety of goods and services. As individuals, none of us is capable of producing all that we consume. We are necessarily forced to produce only a very limited (often only one) kind of goods and services. We exchange what we produce for the wide variety of things we consume.

This exchange of one person’s production for a variety of consumer goods from other persons could be effected through barter but barter is prohibitively expensive in terms of time and effort because it necessitates many “double coincidence of wants.” Therefore we use money as an intermediate good. I get money by selling whatever I produce and use the money to buy what I consume.

This buying and selling is critical to our survival as individuals and, by extension, as a society.

A parsimonious description of economics is that it is the systematic study of exchange or trade. Also, because humans are the only life form on earth that trade, economics is the study of humans engaged in trade. Only we humans trade. Adam Smith (1723 – 1790) wrote, “Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog.”[1]

If two parties engage in what is called free or voluntary trade — trade that does not involve force or fraud — it must be logically true that each party believes (perhaps mistakenly) that he will be better off after the trade than before. Both parties therefore necessarily stand to gain from free trade.

Without being too pedantic about it, the simple conclusion follows that societies that allow and enable free trade are relatively more prosperous than societies that restrict trade.

A stark example of the power of trade consider the case of North Korea versus South Korea. North Korea is autarkic. It does not engage in international trade; South Korea does. North Korea is a desperately poor country with nuclear weapons; South Korea is a rich country.

Trade among people within a nation is obviously distinct from international trade. Or is it?

We hear of nations trading but the truth is that nations don’t trade; people do. Individuals and firms of one nation trade with individuals and firms of other nations. There is no essential difference between domestic and foreign trade. Regardless of whether domestic or international, restrictions on free trade lead to welfare losses.

As a consumer, I don’t particularly care where in the world the phone was manufactured; what matters to me is whether I value the phone more than the money I have to shell out for it.

The above-mentioned Adam Smith is considered the father of classical economics which is dated with the publication of (short name) “The Wealth of Nations” in 1776. He and his contemporaries understood well the welfare consequences of trade. They also understood that the bigger the market size, the larger the gains from trade, the division of labor and specialization.

With international trade, markets for goods and services are larger than they would be otherwise. Therefore it is economically more efficient to have international trade.

Comparative Advantage

The question of why trade leads to welfare gains was put on a sound theoretical foundation by the British economist and politician David Ricardo (1772–1823) (and a few others) in his theory of comparative advantage, developed in 1817. It explains how countries can benefit from trade by specializing in the production of goods they can produce at a lower opportunity cost compared to others.

The concept “opportunity cost” is important and should be more widely known. It means that the true cost of doing something is what one has to give up doing other things. Suppose one could choose to do one of three things: A, B or C. The opportunity cost of doing A is the foregone net benefit of doing B or C.

Quick example. I could spend two hours watching a movie. The cost of the movie ticket is $20. Instead of spending two hours at the movie (activity A), I could have worked at McDonald’s for two hours (activity B) and earned $30, or I could have done two hours of research (activity C) worth $200. Then the opportunity cost of going to the movies is $200 (the foregone earnings from research) and the total cost of the movie is $220, not just the $20 ticket price.[2]

This concept of comparative advantage suggests that even if one country is more efficient in producing all goods, trade can still be mutually beneficial if each country focuses on its relative strengths.

To make this idea concrete, let’s suppose that using a certain amount of labor, the US can produce either 400 shirts or 200 shoes. Let’s also suppose that using that same amount of labor, Mexico can produce either 300 shirts or 100 shoes. By construction the concocted numbers are meant to show that the US is more efficient in producing both shirts and shoes compared to Mexico. We say that the US has an absolute advantage over Mexico in producing both shirts and shoes.

Now consider the opportunity costs. In the US, the opportunity cost of making a shoe is two shirts, or stated conversely the opportunity of making a shirt is half a shoe. In Mexico the opportunity cost of making a shoe is three shirts; conversely the opportunity cost of making a shirt is one-third of a shoe.

Shirts are more expensive in terms of shoes in the US. Shoes are more expensive in terms of shirts in Mexico. The US has a comparative advantage in producing shoes, and Mexico has a comparative advantage in producing shirts. Therefore for maximizing the production of shoes and shirts, the US should specialize in producing shoes and Mexico should specialize in producing shirts, and if they trade shoes and shirts, they both will be better off than they would be otherwise.

Since this is a blog post and not a chapter in a textbook on trade, I am not going into what the prices of shirts and shoes will end up being in US dollars or Mexican pesos. Regardless of what those realized prices end up being, the gains from trade are undeniable.

The distinction between comparative and absolute advantage is important and appears deceptively easy. But comparative advantage is often misunderstood even by smart people. Tread carefully.[3]

In the US-Mexico example above, we were talking about international trade. But if you think about it, the notions of opportunity costs, absolute advantage and comparative advantage apply to all trades, not just trade across national boundaries.

The house cleaner and the brain surgeon enjoy the gains from trade because they have their respective comparative advantages, regardless of their absolute advantage.

The mutual gains from trade could be the motivation for trade. Or perhaps there’s a deeper instinct in the human heart, “a certain propensity in human nature . . . the propensity to truck, barter that compels use to trade and exchange.”[4]

Markets

That propensity to exchange is expressed in what we call the “market.” Markets are where trades take place. It can be a physical space such as a supermarket, or a virtual space such as a website. It could be a “futures market” or it could be instantaneous. Markets come in all sizes and shapes but they all serve a vital function: to realize the gains from trade. The greater the extent of the market, the greater the gains from the division of labor and specialization.

Free Markets

Markets which have no barriers to entry or exit are termed “free markets.” In free markets, anyone can sell to willing buyers, and anyone can buy from willing sellers. No entry barriers means anyone can be a buyer or seller in the market; no exit barriers means anyone can refuse to buy or refuse to sell in the market.

This point is important and worth belaboring. If I am compelled to sell my labor to someone, I am a slave and it is not a free labor market. If I am compelled to hire someone on terms that I don’t agree to, then it’s not a free market. If I am prohibited from selling my product, then it’s not a free market. If I am forced to buy from a particular seller, it’s not a free market.

Most poor countries don’t allow free markets. That explains partly why they are poor. Exhibit A: India.

Free trade consists simply in letting people buy and sell as they want to buy and sell. It is protection that requires force, for it consists in preventing people from doing what they want to do. Protective tariffs are as much applications of force as are blockading squadrons, and their object is the same—to prevent trade. The difference between the two is that blockading squadrons are a means whereby nations seek to prevent their enemies from trading; protective tariffs are a means whereby nations attempt to prevent their own people from trading. What protection teaches us, is to do to ourselves in time of peace what enemies seek to do to us in time of war.

-

-

- Henry George (1839-1897). American free trade on how protectionism harms domestic consumers (1886).

- Henry George (1839-1897). American free trade on how protectionism harms domestic consumers (1886).

-

There are numerous examples of un-free markets. A “maximum retail price” (MRP) is a government mandated ceiling on the price of products. A “minimum wage” is a floor on the price of labor. Rent control puts a ceiling on rents.

All such mandates prevent mutual gains from trade. Impose enough such restrictions on free trades among people and firms, and you have the perfect formula for impoverishing society and cutting off the route to prosperity.

Barriers to Trade

There are a variety of barriers to trade: taxes, tariffs, prohibitions, quotas, etc. These can be used both in domestic and in international trade. They all end up leading to welfare losses.

Let’s start with taxes. A tax is a “wedge” between the price the buyer pays and the amount the seller receives. The buyer pays more than what he would have paid without the tax, and the seller receives less than what he would have received without the tax.

On the margin, taxes reduce the number of trades, and sometimes, given a sufficiently high tax, entirely eliminate all trades. The technical term for the welfare losses due to taxes is “deadweight loss” — that amount that is lost by the buyer and seller net of the tax revenue.

Certainly, taxes have to be raised for financing essential services. But reckless use of taxes can hinder commerce, retard economic growth and impoverish the nation. Case in point: India.

Tariffs are taxes on imports. Like all taxes, they lead to deadweight losses. Tariffs, just like taxes, raise the price of the good (or service) for the buyer and reduce the revenue to the seller. How much of the tax or the tariff is paid by the buyer and how much by the seller depends on the nature (elastic, inelastic, etc.) of the demand and supply schedules.

Tariffs and taxes raise the price consumers pay. POTUS Trump appears to believe that putting tariffs on imports will force the exporting countries to pay the tariffs and enrich the US is asinine bullshit. I would fail any Econ 101 student for proposing such ignorant rubbish.

Examples of tariffs abound. The US in the early years used import tariffs to raise revenues for government expenses. In effect, the tariffs were an indirect tax on the people since they had no other way such as sales and income taxes.

Tariffs are often politically motivated. Labor unions wish to protect their jobs. Cheaper imports hurt domestic producers. By imposing a sufficiently high tariff, the domestic producers can compete in the domestic market.

But remember that there is no free lunch. The saving of domestic jobs comes at the cost of higher prices that domestic consumers are forced to pay.

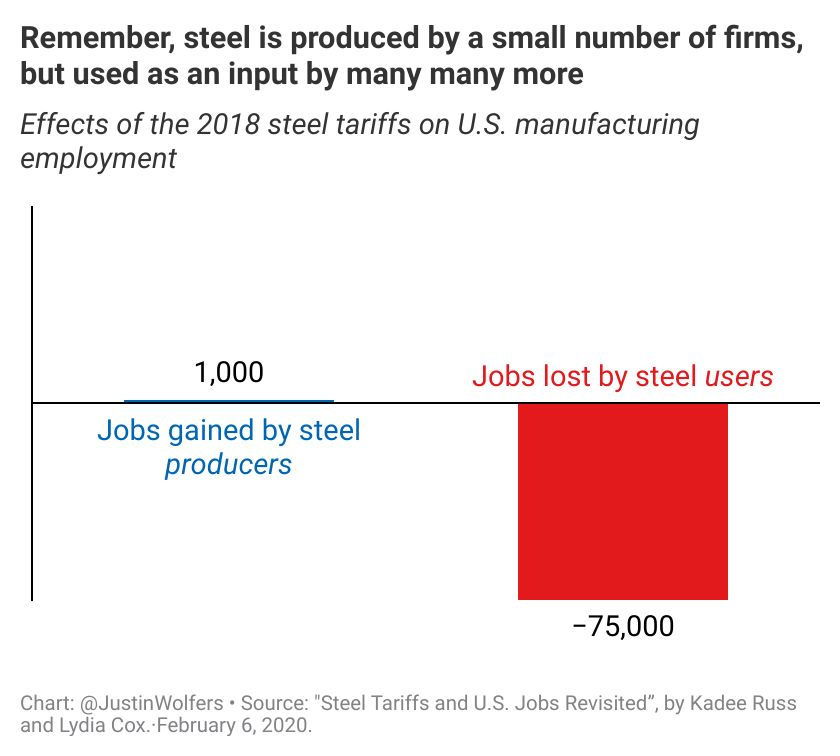

By imposing tariffs on, say, steel imports, domestic steel producers continue to produce steel. But domestic users of steel have to pay a higher price for steel. Steel is an input to other production processes. Thus the cost to the domestic producers of final products that use steel goes up. Those producers find it harder to compete in the international markets.

Domestic producers of steel products thus have to, on the margin, let go of workers. It could be that the job losses in the steel consuming sector are much larger than the jobs saved in the steel production sector.

Here’s a graphic that illustrates that point. Source: Steel Tariffs in Two Pictures.

Import quotas have the same effect on prices for consumers as tariffs: higher consumer prices. But there’s an important distinction. Tariffs raise consumer prices but also raise government revenues. In effect, it is a transfer from the consumers to the government. Import quotas raise consumer prices but don’t raise any revenues: the higher prices translate into higher profits for the exporting industry in the foreign country.

Import quotas have the same effect on prices for consumers as tariffs: higher consumer prices. But there’s an important distinction. Tariffs raise consumer prices but also raise government revenues. In effect, it is a transfer from the consumers to the government. Import quotas raise consumer prices but don’t raise any revenues: the higher prices translate into higher profits for the exporting industry in the foreign country.

Tariffs, quotas and import prohibitions are generally bad because they all inhibit trade. And trade, as we have seen, is good. But it is generally believed that exports are good for the economy and imports are bad for the economy. If the dollar value of a country’s exports is lower than the dollar value of its imports, then it has a trade deficit. The general belief is that a trade surplus is good, and trade deficit is bad.

The general belief is not correct. I will leave that for later.

That said, it is undeniable that matters are not that simple.

Second-best World

Free markets and free trade — domestic and international — are policy options in a first-best world. A first-best world is one in which there are no distortions. If a distortion arises in a first-best world, all you have to do is to impose a first policy and the world is back to being first-best.

However, we live in a second-best world — a world that has multiple distortions, say three. In such a scenario, applying policies to fix those distortions could as well make the situation worse. You either figure out how to address all three distortions simultaneously or don’t think that you can improve the situation by piece-meal solutions. In a second-best world, it could even be that introducing an additional distortion (which would not be recommended in a first-best world) improves the situation.

Taxes, tariffs, quotas and prohibitions could be justified,under certain restrictive conditions, in a second-best world. Trade with unfriendly nations could justify imposing barriers to trade.

(Continue to Part 2 of this post.)

NOTES:

[1] “Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog. Nobody ever saw one animal by its gestures and natural cries signify to another, this is mine, that yours; I am willing to give this for that. … But man has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only. He will be more likely to prevail if he can interest their self-love in his favour, and show them that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them. Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of.”

Adam Smith. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations ― (1776)

[2] When doing this sort of cost calculation, one has to be careful to calculate the net benefits — that is benefits minus costs. Suppose going to the movie gives me $150 worth of utility (enjoyment), and the disutility of doing research is $100. What should I do? This is left as an exercise for the interested reader.

[3] I like to repeat the story of the mathematician Stanislaw Ulam and Paul Samuelson. Ulam once asked Samuelson if there was anything in economics that was both non-obvious and true. Samuelson took several years to arrive at the answer that it was the theory of “comparative advantage.” He said, “That it is logically true need not be argued before a mathematician; that is not trivial is attested by the thousands of important and intelligent men who have never been able to grasp the doctrine for themselves or to believe it after it was explained to them.” [See this post.]

[4] “The division of labour, from which so many advantages are derived, is not originally the effect of any human wisdom, which foresees and intends that general opulence to which it gives occasion. It is the necessary, though very slow and gradual consequence of a certain propensity in human nature which has in view no such extensive utility; the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.”

Adam Smith. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Book 1, chapter 2.

A lot of what you wrote till now needs to be revised after this realization that we live in a second-best world.

LikeLike

In a second-best world, we have to avoid first-best policies.

LikeLike