Freedom is essential not just for material prosperity but more importantly because it defines our humanity. We are not fully human if we are not free. Being free to live one’s life as one wishes, to protect oneself and one’s family, to engage in an occupation of one’s choice, to freely associate — or not associate — with others, etc., are aspects of what we mean by human freedom. Of these, the freedom of speech and expression is invaluable.

Freedom is essential not just for material prosperity but more importantly because it defines our humanity. We are not fully human if we are not free. Being free to live one’s life as one wishes, to protect oneself and one’s family, to engage in an occupation of one’s choice, to freely associate — or not associate — with others, etc., are aspects of what we mean by human freedom. Of these, the freedom of speech and expression is invaluable.

Freedom is a modern concept. For all of human history and for every people, unfreedom was the norm. It is only in the last few centuries, and only in some parts of the world, and only in some limited sense have some people been free. It’s a depressing realization. Perhaps as time goes by, more people will become free. But that hope appears to be fading if one goes by what’s going on in the UK.

Ironically, the British have been at the vanguard in the promotion of freedom of speech. Prominent are the “Johns” — John Milton (1608–1674); John Locke (1632–1704); John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). Mill’s work, “On Liberty,” (1859) is a classic defense of the right to freedom of expression. Then we have David Hume (1711–1776) and Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679).

The Founding Fathers of the United States were influenced by these philosophers. That’s why the first item on the US constitution’s “Bill of Rights” reads, in part that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press . . . “

Americans. Their freedom of speech and of the press is in no small regard instrumental in their success.

But back to the UK. The UK is steadily regressing to an earlier time when people could not say what they thought or believed in. This is regrettable. Their own public figures have been speaking out in recent time. Here Christopher Hitchens:

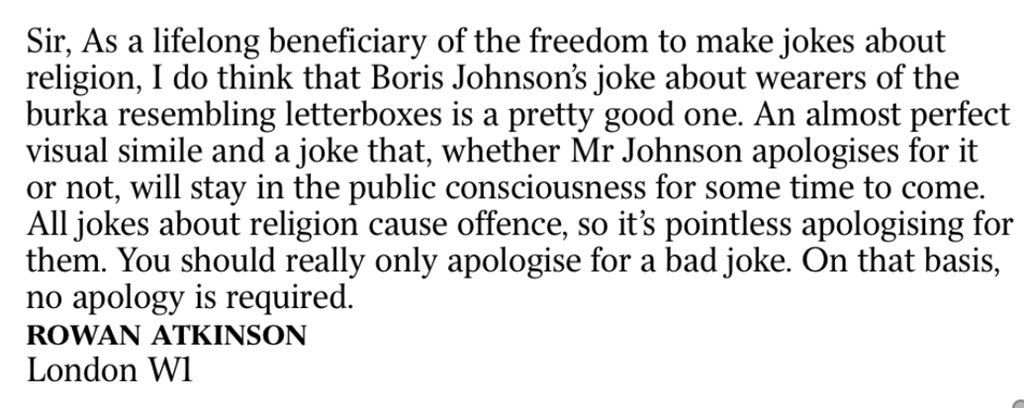

And here’s Rowan Atkinson in October 2012:

Though Hitchens is no more, the good news is that there’s Douglass Murray to continue carrying the flag of freedom.

For further reading. My post from July 2016, “Speaking of Freedom of Speech.” In a comment to that post, I was asked a few questions. I replied to those thusly:

Freedom of speech, in my opinion, is an absolute. There must not be any restrictions on speech. Under no circumstances must anyone be prevented from speaking (which includes writing, or any other form of communicating ideas, thoughts, etc.)

Q. Should one be allowed to lie?

A. First we have to define what it means “to lie.” If I say, “The sky is bright pink”, is that a lie? Certainly it is because it is obviously blue except due to some atmospheric conditions it appears to be a bright pink. Whether it is blue or not is a matter of evidence. What ever be the fact, the mere expression of that lie (if that be so) is harming no one.

Is it a lie for me to say that I think Facebook sucks? You may disagree but it’s my opinion. I should be free to express my opinion.

What if I say, “Ashok is a rapist.” Is that a lie? Depends on whether Ashok has in fact committed rape. Should I be allowed to make that claim? Yes. Is Ashok damaged by my claim? Yes, if indeed he’s innocent. If so, then he has recourse to making me pay for libel. But a priori I should not be prevented from making that claim.

Should I be allowed to shout “fire” at any point? Yes. But if there is no fire and my raising of a false alarm causes a stampede, I am liable for damages caused. What if I raise the alarm that the house is on fire, and indeed it is, am I liable for the broken leg of someone who panics and instead of taking the stairs, jumps out of a second floor window?

All these are specific cases that raise interesting questions. But the principle of free speech is unaffected by corner cases.

The principle of free speech arises from a deeper philosophical position — that of the freedom of the individual. It is not an utilitarian argument even though free speech has immense social utility. I will not go into those bits here.

Human fallibility is another practical reason why freedom of speech is an absolute. No human is all-wise and all-knowing. So who is to judge whether what I say is wrong or right? Who are you going to put in charge to decide what should be allowed and what disallowed when it comes to speech?

Q. Should speech that helps terrorists be allowed?

A. Sure. But remember that helping terrorists may make you liable to damage from the victims of terrorists. So whether you do it by speech (by radioing them facts that help them) or by supplying them with ammunition, you are involved in a criminal activity.

Free speech allows you to say what you want but it does not mean that it protects you from any criminal activity you undertake. You are free to speak what you will but you are not free from the consequences that may follow.

Q. Should people have the freedom to consume drugs?

A. Sure. If I want to ingest something, I don’t see why anyone else should prevent me from that. I am a free person, not a slave or a serf. If I wish to buy drugs (legal, illegal, harmful, beneficial, whatever), and someone is willing to sell them to me, I don’t see how a third party has any rights to interfere.

The problems that humanity faces are many, and each of them have many causes. The majority of these, I think, have one thing in common: one of the major causal factors is needless interference in the affairs of individuals by third parties. I say to those stupid busybodies, “Fuck off. It’s none of your business.”

Finally, for the seriously interested on the philosophical idea of the freedom of speech, a great resource is entry Freedom of Speech in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. It starts with:

Human beings have significant interests in communicating what they think to others, and in listening to what others have to say. These interests make it difficult to justify coercive restrictions on people’s communications, plausibly grounding a moral right to speak (and listen) to others that is properly protected by law. That there ought to be such legal protections for speech is uncontroversial among political and legal philosophers. But disagreement arises when we turn to the details. What are the interests or values that justify this presumption against restricting speech? And what, if anything, counts as an adequate justification for overcoming the presumption? This entry is chiefly concerned with exploring the philosophical literature on these questions.

Be well, do good work, and may your god go with you.

I used to be a free speech absolutist until recently – now I say one’s attitude towards a certain philosophyor ideology which goes totally against one’s own free speech values should be what adherents of said philosophy would do if they were in the driving seat instead of oneself. It’s why the long march through the institutions was able to happen in the West, why there was a CPUSA and no such thing as a liberal party (or indeed any other party) in the communist states.

In the so called but non existent ‘marketplace of ideas’, all ideas in theory ought to be challenged. Unfortunately right-wingers/conservatives have actual job and family responsibilities that take precedence over organizing to counter the left. Here in Sydney I keep seeing posters for conferences on Marxism and anti capitalism, run by the usual jobless lefties ranting against the system. There’s nobody to counter their bullshit rhetoric because there are none like that in the universities, and those that do support libertarian or conservative ideas (lower taxes, liberty, small govt etc) tend to be small business owners and the like, who don’t organize or spend time to spread their ideas.

LikeLike