Growth is a feature of the natural world. All sorts of processes at various scales — from the molecular to the galactic — lead to growth. Plants and animals grow through their life cycles, as do stars and galaxies. The opposite process of degrowth is also part of the natural world. Growth invariably leads to dissolution and death. Nothing lasts forever. Whatever has a beginning has an end. Creation and destruction are inextricably linked. Shiva, as Nataraja, ceaselessly dances the universe into existence and also dances it out of existence.[1]

Growth is a feature of the natural world. All sorts of processes at various scales — from the molecular to the galactic — lead to growth. Plants and animals grow through their life cycles, as do stars and galaxies. The opposite process of degrowth is also part of the natural world. Growth invariably leads to dissolution and death. Nothing lasts forever. Whatever has a beginning has an end. Creation and destruction are inextricably linked. Shiva, as Nataraja, ceaselessly dances the universe into existence and also dances it out of existence.[1]

Though growth and its opposite continue, overall growth wins over degrowth. The universe and its various subsystems grow with the passage of time.

Narrowing our focus to the processes that are involved in the evolution of life on earth, we see the same cyclical story: birth, growth, dissolution and death followed by renewal. All these processes are by definition dynamic and therefore have the potential to be creative.

Narrowing our focus even further, we consider us humans and what we do. Economic activity consists of production, exchange and consumption. Economic growth is the intensification and enlargement of economic activity. It’s helpful to have some agreed upon measure of economic activity. A commonly used metric is GDP. It measures the total amount of production in a specific period (a year) by a particular collection of people.

Is there a limit to economic growth? At first glance, there must be a limit since unlimited growth is not possible in a finite system. But we have to ask what defines the limit and what is that limit. Are we anywhere close to it, and if we are, what can we do about it, and what should we do about it?

The position I defend here is that there are no practical limits to growth because the earth, though a finite system with well-defined boundaries, is not a closed system. It’s not a closed system because it receives energy from the sun, and radiates energy into space. We humans use energy to power our economic system and grow it. Since the supply of energy is limitless for all practical purposes, economic growth too is limitless.

This view is contrary to our natural instincts. We have never witnessed anything grow limitlessly. We’ve seen things grow big but eventually they die. Therefore, we reason, surely economic growth must also come to an end. We further believe that since we have had so much economic growth already, we must have transgressed the natural limit and therefore we must now immediately turn around to avoid catastrophe and death.

But this reasoning is wrong because of two wrong assumptions. One has to do with the assumption of the lifespans of entities, and the other has to do with the availability of energy. Both are indefinite and limitless.

Certainly, individuals pass away but the larger entities at levels higher than the individual persist for very long periods. Even particular civilizations come and go in time scales of a few thousand years but the entire human enterprise continues for hundreds of thousands of years.

Let’s explore this idea of the death of subsystems but the persistence of the larger organism in the context of an economy. A firm is a collection of people involved in some particular economic activity; a collection of firms of a specific type defines an industry; a collection of industries defines an economy.

An example. Toyota is a firm in the automobile industry which consists of GM, Honda, Tesla, etc. The auto industry is one of hundreds of industries in large economies. Firms enter and exit industries; industries enter and exit economies. Birth, growth and death of firms, industries and economies goes on much like the birth, growth and death of organisms, species and ecosystems in the natural world.

At every level, competition is relentless. Though competition is not good for any particular individual or entity, it is good for the system. The death of a firm is not good for the firm but is good for the industry; the death of an industry is good for the economy. Evolution is the dynamic dance of creation and destruction. To have good things today, we have to let go of the things of yesterday.

I marvel at the fact that most of the industries we have today did not exist a couple of hundred years ago. Here are two modern examples. Commercial aviation industry is barely one hundred years old but it transports billions of people every year. The ubiquitous computation and telecommunications systems we use every day came into existence just a few decades ago.

So what is the magic ingredient that brings all good things to life? It is energy. It is needed for the sustenance and growth of all things. The economy can grow indefinitely given energy. The good thing is that energy is not limited because humans create knowledge that enables them to harness energy. Energy cannot be created, of course, but it can be harnessed.

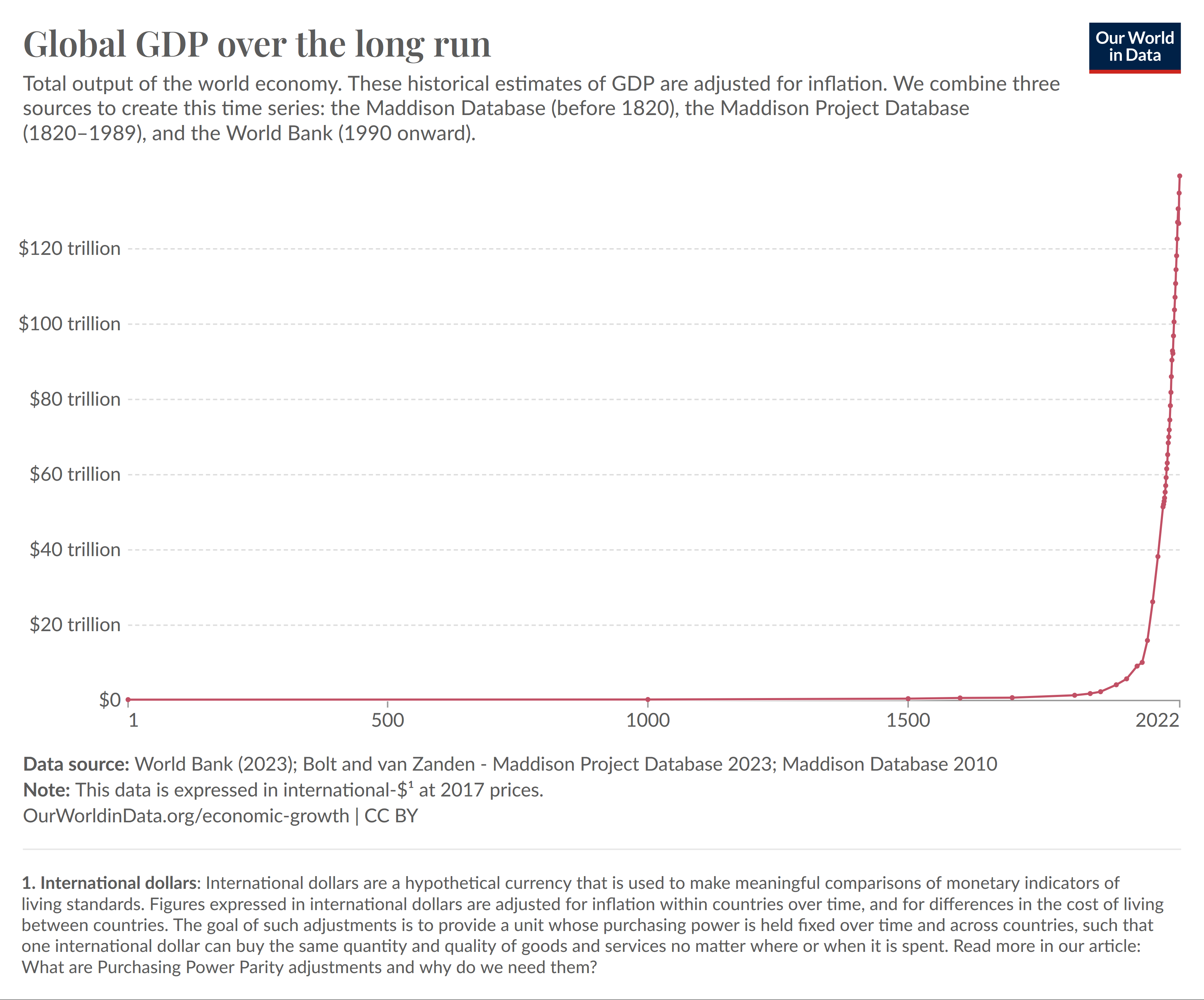

A quick review of economic growth is instructive at this point. Economic growth of the world is illustrated by a simple graph: Global GDP over the long run. The story it tells is astonishing.

From the graph above, we note this. The world GDP in the year 1 CE was $213 billion; in the year 1000 it was $245 billion. That’s an increase of only $32 billion in 1000 years, which is close to a zero GDP growth rate per year. World GDP rose to $502 billion by the year 1500 CE. That is still close to zero annual GDP growth rate. By 1700, it had risen to $752 billion. It had doubled to $1.4 trillion by 1820. That’s respectable but still nothing to write home about. Then it took off after that. By 1900, it was $4.2 trillion; then in the following 80 years, the world GDP tripled. By 1950, it more than doubled to $10.1 trillion. Then in 30 years, by 1980, it had nearly quadrupled to $38 trillion. In 2022, world GDP was close to $140 trillion dollars.

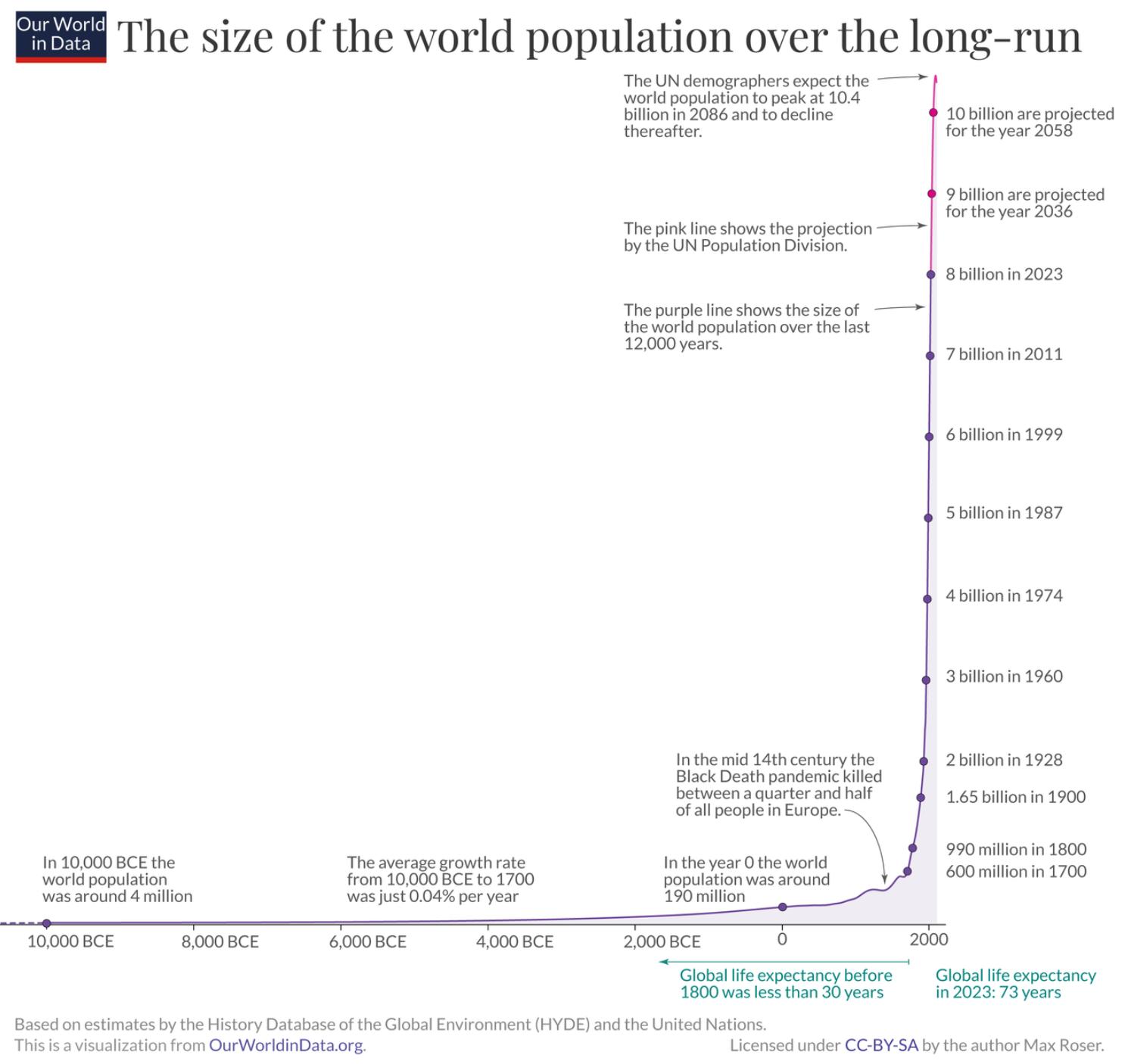

What led to that explosive growth after the year 1820? A clue to the answer is in another graph that charts the growth of human population.

Here are a few numbers from the graph. At the start of the CE, the world population was around 190 million; by the year 1800, fewer than 1 billion; 1900 — 1.65 billion; 1960 — 3 billion; 1987 – 5 billion; 2011 — 7 billion; 2023 — 8 billion.

Note that both the graphs have the same hockey stick shape: practically no change in the slope (the handle) and then suddenly a sharp upturn (the blade.) That the shapes match is no coincidence. The two factors are causally linked. Not just that, they are bi-directionally linked. More people leads to greater economic growth; and greater economic growth leads to a larger population. This is an example of a positive feedback process.

The simple story is that humans create economic wealth using naturally occurring materials (found on and close to the surface of the earth), technology and energy. The more people there are, the more technology is created. As technology grows, so grows the ability to harness new sources of energy. The economy grows as our energy use grows. The more the economy grows, the more humans prosper.

For all of human history, the vast majority of humans have lived in extreme poverty. Even as late as 1950, around half the world’s population lived in extreme poverty; now that figure is less than 10 percent.

However, although escaping extreme poverty is good, it is a very low bar. There are billions still trapped in ordinary poverty. We have the means to lift them up in the next decade. Provided we don’t get taken in by the degrowth crowd.

Therefore people who think that we have reached some limit to growth are unaware that there is no limit to energy discovery and use. But being mistaken about the nature of the world is not a crime. Being stupid and ignorant is distressing to all concerned but it is not a crime. What is a crime is to force others to one’s whims born out of stupidity and ignorance.

The people who are advocating degrowth are culpable of attempted crimes against humanity. Allow me to explain.

[What is degrowth? I have attached a note at the end of this piece. I don’t define it here to keep this bit uncluttered. See note #2.]

People who are promoting the false idea of limits to growth are guilty of keeping hundreds of millions of humans in needless material poverty. No poor person would support the idea of continued poverty. They seek the same kind of comfortable lives that the rich enjoy today. That’s reasonable and fair.

All of these degrowth people are rich and comfortable, of course. They fly around the world in their private jets to World Economic Forum conferences in lovely places. They then proceed to lecture the world’s poor that they have to curtail their already meager consumption to save the planet from imminent catastrophe. They push rules that they themselves flout. Rules for thee but not for me. Do as I say, not as I do.

It would be nice to see them curb their consumption. It would be nice to see them use public transport instead of private jets and yachts. It would be nice to see them give up their immense mansions and live where the less fortunate do.

I don’t envy the rich or even the filthy rich their wealth. Some of them, though not all, have done something to deserve what they own. Gates, Zuckerberg, Bezos, Musk and their ilk certainly didn’t sleep their way to their fabulous wealth. What I do resent is when the super wealthy start pontificating. They all should get off their moral high horses and stop their hectoring.

In this business of lecturing the public there’s close competition between the leftists and the politicians. Every country has them and their numbers are constantly increasing.

But I am an optimist. I believe that people will understand that there is no reason to take the degrowth crowd seriously. People will realize that the world is on track to attain unimagined and unimaginable levels of prosperity and growth. In the end, the good guys will win.

In a more comprehensive piece, I will note that growth can happen without increase in material throughput. This is known as “dematerialization” — we use less material to achieve the same utility. IBM’s 5mb hard drive from 1956 was as large as a modern 3-door fridge. Today you can fit a 5tb drive in your shirt-pocket. That’s a 100 million times less material for the same utility.

Acknowledgement: This post was brought to you thanks to generous support from a non-economist friend who envies the smarts that economists have.

NOTES:

[1] There’s a lovely description of the Nataraja here: Tandava, Shiva’s Cosmic Dance. It’s from Heinrich Zimmer’s book Philosophies of India.

[2] From the wiki article on “Degrowth”:

Degrowth is an academic and social movement critical of the concept of growth in gross domestic product as a measure of human and economic development. The idea of degrowth is based on ideas and research from economic anthropology, ecological economics, environmental sciences, and development studies. It argues that modern capitalism’s unitary focus on growth causes widespread ecological damage and is unnecessary for the further increase of human living standards. Degrowth theory has been met with both academic acclaim and considerable criticism.

Degrowth’s main argument is that an infinite expansion of the economy is fundamentally contradictory to the finiteness of material resources on Earth. It argues that economic growth measured by GDP should be abandoned as a policy objective. Policy should instead focus on economic and social metrics such as life expectancy, health, education, housing, and ecologically sustainable work as indicators of both ecosystems and human well-being. Degrowth theorists posit that this would increase human living standards and ecological preservation even as GDP growth slows.

Degrowth theory is highly critical of free market capitalism, and it highlights the importance of extensive public services, care work, self-organization, commons, relational goods, community, and work sharing. Degrowth theory partly orients itself as a critique of green capitalism or as a radical alternative to the market-based, sustainable development goal (SDG) model of addressing ecological overshoot and environmental collapse.

Atanu,

You are right that energy is not an immediate limit to growth. While total energy usage today is about 20 TW (20E12 Watts), solar energy received by Earth at any given time is about: pi * R^2 * Solar_constant = 3.14 * 6.378E6^2 * 1.361E3 = 173843 TW. So, yes there is enormous room for growth in energy usage.

However, as most serious proponents of the limits-to-growth point out, the most immediate limit-to-growth is the ability of the biosphere to absorb the wastes generated by the industrial capitalist economy, starting of course with the most well known carbon-dioxide/green-house gases limit.

While in theory, enough energy exists that can be used to absorb and detoxify these massive wastes, the current political-economic system has shown itself to be incapable of organizing this: tax-the-polluter: fail; carbon-credits: fail; etc.

We also need to ask the fundamental question: Why does the capitalistic economic system require endless growth as a mandatory feature? While growth is natural, as Vaclav Smil points out, most natural systems grow, then remain stable (zero growth) for long periods and then degrow. Zero growth however is lethal for the capitalist system, not matter the GDP level at which the growth ends.

The demand for endless growth is the root of all our problems.

“Exponential economist meets finite physicist” lays it out well:

https://dothemath.ucsd.edu/2012/04/economist-meets-physicist/

LikeLike

The author is a pseudo-scientist who ran away from Engineering and from actual work. Don’t expect honest engagement, just grandiose concepts from an Ayn Rand bhakt.

LikeLike

It’s not that hard to insult someone in their own turf. Try making an argument to make your point instead of slinging mud. If you think that “Ayn Rand bhakt” is a devastating blow against someone’s argument, you have much to learn. Try the San Jose public library. There must be one very close to where you live.

LikeLike

Akshay. All your points require a somewhat detailed answer. I will do that in a post today. Thanks for your comment.

LikeLike