Let’s start with a story.

Let’s start with a story.

Once upon a time, so the story goes, a king got mightily upset with one of his ministers and sentenced him to death. The minister pleaded for his life and promised the king, “If you let me live, I will invent a flying horse in five years, and you’d become very powerful.” The king agreed to spare his life if he invented a flying horse.

The minister went home and told his wife of his narrow escape. She said, “Oh how terrible. How on earth are you going to invent a flying horse?” He said, “Don’t worry. Five years is a long time. The king might die in the meanwhile, or I might die, or someone may invent a flying horse. Who knows what will happen in five years!”

TL;DR Summary

The global hysteria whipped up by certain groups regarding climate change is fascinating. It represents a toxic mixture of politics, economics, science, ignorance, myopia, stupidity, fear, hubris, technology, power dynamics, racism, benevolence, malevolence and arrogance.

Climate is changing, as it always has. The data show the rise in temperature. Humans affect climate. Humans adjust to change too. Technological advances in the near future will allow humans control over the environment. Doing anything to control C02 emissions now by edict will be too expensive, be extremely harmful to the poor, will shift resources from other important matters, and have no discernible benefits for future generations.

Pattern Prediction

That flying horse story refers to one basic truth about the world: the future is unknown and unpredictable in any detail wherever people are involved. You can predict with astonishing precision how some non-living system will evolve. Predicting eclipses, for instance the total solar eclipse of 21st Aug 2017, is easy. But predictions relating to systems of living beings endowed with will and volition is not possible with any degree of precision.

We can roughly predict what patterns are likely to emerge in some specified short period but beyond that time horizon, we cannot see. Furthermore, as human civilization has advanced, the time horizon within which meaningful pattern prediction can be made has shrunk. The reason is technology, a point that I explore below. The non-human natural world is more predictable than the world in which humans exist because humans are inventive.

Shrinking Time Horizons

Imagine an alien visiting the earth 50 million years ago and noting the state of the world. If it were to revisit a million years later, it would find little had changed in the meanwhile. The prediction time horizons would be millions of years. There were no humans around then.

Imagine the alien visiting earth 100 thousand years ago, when human walked the earth, and then again visiting 10 thousand years later. Once again, it would notice little change. Humans were around but they had almost no technology.

Now imagine the alien visiting earth 1000 years ago, and returning a 100 years later. It would observe some change but not much to write home about. Humans then had only pre-industrial age technology which was quite primitive by our current standards.

Aliens and Technology

For most of human history, little changed. Humans advanced technologically at a pace that was barely noticeable. The taming of fire, the invention of the wheel, discovery of the base-10 positional number system, the invention of writing, etc., occurred over a span of thousands of years. People lived lives that were not much different from the way their ancestors lived, and the way their descendants would live. The prediction time horizon would have shrunk to hundreds of years in the relatively recent past.

Imagine the alien visitor (who has by now racked up many frequent visitor points) visiting in the year 1900, and revisiting in the year 2000. It would have seen changes it could not have imagined. This time ET would have something to call home about.The prediction time horizon would have shrunk to mere decades. Humans had developed advanced technology.

Two factors contribute to the shrinking of time horizons. One is the increase in human population and the other, a consequence of the first, an increase in the rate of growth in the stock of technology.

Human Population Growth

It took all of human history — around 200 thousand years — for human population to cross the 1 billion mark around the year 1800. The next billion was added in 130 years, and the next in 33 years. It took only between 12 to 14 years to add the subsequent billions. Now there are 7.5 billion people on earth.

It took all of human history — around 200 thousand years — for human population to cross the 1 billion mark around the year 1800. The next billion was added in 130 years, and the next in 33 years. It took only between 12 to 14 years to add the subsequent billions. Now there are 7.5 billion people on earth.

The rate of population growth has slowed but the numbers are likely to increase throughout this century till it reaches a peak of around 10 billion.

The question “how many people can the earth support” is surprisingly hard to answer. Clearly it is not infinite but the range is remarkably wide — from the present 7.5 billion to maybe 100 billion.

It is true that the more people there are, the greater is the impact on the environment — the life-support system — of the world, for a given level of technology. The more advanced the technology, the more people can be accommodated for a given level of environmental impact. Today’s 7.5 billion at the present quality of life could not have been possible with the year 1800 technology.

Today around 2 billion (of the 7.5 billion) people live lives that would have been unimaginable in the year 1800 (when the entire global population was only 1 billion.) Not a single person in the year 1800 had the kind of creature comforts, opportunities, life expectancy, etc., that are commonplace to billions today.

No one could come close to predicting in the year 1900 even in broad terms what the world would be like in the year 2000. Certainly they attempted to guess what life would be like 100 years in the future. Read this Ladies Journal article and marvel how silly they imagined the year 2000 to be like.

If their 100-year prediction sounds silly, we should be cautious in our own attempts at predicting what the world would be like in the year 2100. Forget 100 years, we would be lucky if we could predict what’s going to happen in 50 years. The prediction time horizon has shrunk to mere decades now.

Why? Because technology is unpredictable. Which brings me to the question of what precisely is technology.

Technology as Know-how

It is easy to think of technology as gadgets and gizmos and fancy electronics and self-driving cars and GPS and smart phones. That’s not quite accurate. The more reasonable way to think of technology is simply as “know how.”

Technology is knowing how to do something. All technological artifacts — cars, planes, phones, fMRI machines, you name it — are the result of knowing how to do something. You know how to build a fire? You have fire technology. You know how to grow rice? You have rice technology. You know how to build a nuclear reactor? You have nuclear technology.

If you don’t know how to do something today, it means you don’t have the appropriate technology. Nobody knows how to generate energy through controlled nuclear fusion today but someone in the future will figure out how and that is when you will have the technology.

Technology is unpredictable because the prediction of technology is a logical impossibility. Correctly predicting future technology amounts to knowing now how something will be done in the future, and therefore you know it already, and therefore it is not in the future. It also logically follows that since the technology of, say, the year 2100 is unpredictable, the state of the world in the year 2100 is unpredictable.

Division of Labor and Know-how

Whenever I consider a technological artifact, my mind always registers it as “someone knows how to do something.” Know-how implies the existence of someone who knows. And until someone knows, there is no technology.

There are 7.5 billion people on earth, give or take a few. Each one of them knows something but no one knows everything. Fortunately, it is not necessary for anyone to know everything.

I often marvel at this fact: no one really knows everything that must be known to build a commercial jetliner, or a smart phone, or any other non-trivial bit of modern technological artifact. No one can build any modern technological artifact unassisted by others.

Imagine a horse cart, a human artifact that was commonly used just a few human generations ago. One person, unassisted, could have built one from scratch. (Scratch means things that are found on or near the surface of the earth.) No doubt he would have had to learn how to make the cart from others, but he could retain that in his head and get the job done by himself, using only wood and other nature provided stuff.

But let anyone attempt to build a car from scratch. There’s not enough time in a human lifetime to learn all that a person has to know to build a car from scratch, and even if a person knows it all, he cannot do it all by himself.

The same goes with even greater force for commercial jetliners and smart phone and computers, etc. So how on earth do these things get built at all? Because of the division of labor and the aggregation of dispersed knowledge.

The making of a commercial jetliner involves about a gazillion (an unspecified number larger than whatever you might guess) separate bits of know how. Each of those bits is known to some person(s), and all the bits are known collectively. No single person knows how to build a turbo fan jet engine but collectively the people at companies like GE, Rolls-Royce, and Pratt and Whitney do.

Actually, they know only part of it. They know how to fashion, for instance, the titanium fan blades out of ingots but they don’t really know how to manufacture titanium ingots. Manufacturing titanium ingot from ore is some other company’s job. And of course, mining the ore is some other company’s business. There’s division of labor. And the equally important division of know how.

Markets Aggregate Know-how

We all possess small bits of know-how, and we exchange that to get all the stuff we need to survive but don’t have the time or the know-how to make it ourselves. Each of us, with our little bits of know-how adds a small bit to the process of making something, and in exchange for our contribution we get a bit of what others have contributed to making. The programmer writes a program and earns an income (an exchange) and then uses that income to buy (exchange) cars, and shoes and other stuff that he has not directly contributed in making.

We all possess small bits of know-how, and we exchange that to get all the stuff we need to survive but don’t have the time or the know-how to make it ourselves. Each of us, with our little bits of know-how adds a small bit to the process of making something, and in exchange for our contribution we get a bit of what others have contributed to making. The programmer writes a program and earns an income (an exchange) and then uses that income to buy (exchange) cars, and shoes and other stuff that he has not directly contributed in making.

There are gazillions of exchanges going on constantly across the world, and that is what maintains the world of humans. The exchange mechanism is called the market. The market enables the aggregation of dispersed knowledge into products and services that people value.

Billions of Goodies

How many products and service are we talking about here? I am tempted to say gazillion, and I’d be right. But seriously, is there some way of estimating the lower and upper bounds of the number? Let’s start by asking how many items does Amazon sell in the US? One website reports that (as of April 2017) Amazon’s catalog has 332 million products. The largest category is electronics with 97 million products, of which 63 million are phones and accessories.

Amazon is a very big store, perhaps the biggest in the world. But it does not carry every manufactured product the world produces. They don’t sell cars, boats and planes, for example. So let’s just conservatively estimate that three times as many distinct consumer products exist in the world as is sold by Amazon. That brings the number of distinct items to an even 1 billion products.

But wait, there’s more. We have to add all sorts of intermediate products that go into the production of final products. A modern jetliner has tens of thousands of intermediate products that are unique to jetliners, for instance. Therefore, to the list of final products, add another 500 million intermediate products. So we humans collectively produce 1.5 billion intermediate and final products. That boggles the mind.

I did a quick survey of the stuff in my dwelling and estimated that I have around 500 distinct item categories, and a total of 3000 items (with duplication). That’s a whole lot of stuff that I have no means of producing myself.

Robinson Crusoe was Poor

Do this thought experiment. Think about Robinson Crusoe on his island. Like all of us, RC would have only a limited knowledge of how to get things done. Which means, he had very limited technology. He could do a bit of hunting and gathering for food, a bit of constructing a primitive shelter out of sticks and stones, . . . and that’s about it. Nothing of what we take for granted — even commonplace things as pen and paper — would be available to him. Basically, his limitations arise from the absence of the division of labor and the lack of knowledge aggregation. There are simply not enough people around to produce all the stuff that we ordinarily take for granted.

Let me repeat the point. Each of us uses thousands of items none of which we can produce ourselves. Yet the system delivers all the stuff we use. None of us can reasonably have the knowledge required to produce what we need but still the system delivers them. This is a most underappreciated fact of our world.

Billions of People

So how much knowledge is involved in creating the modern world of today? And how many people have been involved in the creation and use of the knowledge that is at the foundation of our world of human artifacts, and the political, social and economic institutions?

Let’s start with the number of people. It’s estimated that around 100 billion anatomically modern humans (homo sapien sapien) have ever lived on earth in the past 200,000 years, including the 7.5 billion people alive today. Most of the knowledge (technology or know-how), say 99.99 percent, was developed in the last 1000 years, and 99 percent of that was developed in the last 200 years.

These numbers are just guesses but they are based on the idea that the stock of knowledge grows faster with time because the flow or rate of knowledge creation accelerates. The increase in the flow is an increasing function of the stock of knowledge and the number of people involved in creating additional knowledge.

Tons of Technology

When we say the world is changing rapidly today, what we actually mean is that technology is transforming the world rapidly. The pace of change is faster than it was in the past, and it will be much faster in the future. (The mathematically inclined would say the second derivative of the growth function is positive.)

Of course not all humans participate in the growth of knowledge, although nearly all use and benefit from the creation and use of knowledge in producing the goods and services we use. Let’s arbitrarily assume that one out of 100,000 people adds one unit of knowledge to the stock in a certain time period. So when the human population was 1 million, 10 units of knowledge were added to the stock per period. But now, with 7.5 billion people, the stock of knowledge would grow by 75,000 units in the same time span. That’s not just quantitatively different but qualitatively different as well.

Take one specific field of human endeavor — physics. At the start of human history story, there are zero physicists; in the year 1800 there were (I counted) 1,000 physicists; today there are a million physicists, all of whom have amazingly advanced technologies (compared to any time before) to help generate more physics knowledge.

There are more brains, both in absolute and relative numbers, working on increasing the stock of knowledge in every domain. One of the consequences of this is that things become cheaper with time.

Cheap Products

One trivial example familiar to most at the top of the economic heap is computers. Today one can buy for a few hundred dollars a computer (remember that a smart phone is a very powerful computer) that you can carry in your pocket but which has the computing power of a super computer of a few decades ago which used to cost tens of millions of dollars and was as large a bus.

Things are getting cheaper by the day. How can you tell? By noting that more and more people can afford stuff than ever before, be they cars, computers, food, housing, etc etc. The most important factor that enters into the production of things is energy. Energy is getting cheaper too.

Things are getting cheaper by the day. How can you tell? By noting that more and more people can afford stuff than ever before, be they cars, computers, food, housing, etc etc. The most important factor that enters into the production of things is energy. Energy is getting cheaper too.

In the last 40 years, the price of photovoltaic (PV) cells have dropped from nearly $80 per watt to $0.30 today. In a decade, it might fall to a tenth of what it is today. We can’t predict what the price will be but we can predict the pattern: it will continue to fall.

This much is certain: that the price of energy will continue to fall. Why? Because it has fallen historically, and for the same reasons as before, it will the trend will continue. All products are embodied energy and embodied know how. Energy is becoming cheaper and know how is exploding. The mix is explosively powerful.

Let’s underline one fact of the material world we live in. Everything — PV cells being just one out of a gazillion useful human-made products and services — becomes cheaper with time. That also means that with time, the cost of solving any problem becomes lower. Any problem you can think of can be solved in the future at a lower cost than at present. That fact translates into the fact that the people of the future will be richer than the people at present. Here’s more on that.

The Present Rich and the Future Poor

Energy is an input to the production of everything, as noted before. And therefore everything will continue to become cheaper. At every point in the future, it will be such that the poorest person will be richer than the richest person of some point in the past. Let me spell that out.

At some point in the future of humanity, the poorest person of that time will be richer than the richest person on earth today. And the pattern will continue. The poorest person of some future time will be richer than the richest person of the year 2050, and so on.

This means that the wealth of humanity will continue to increase monotonically and the rate of increase will accelerate. Specifically, aggregate and average human wealth at present is greater than it has ever been in history. Generalizing, the aggregate and average wealth function, AAW(.) has the following form:

AAW(x) > AAW(y) for every x, y pair of years where x>y.

Let’s look at an example. The price of antibiotics in the year 1850 was an unaffordable $Infinite. The technology did not exist. In other words, no amount of money would buy you even one antibiotics pill. A significant number of deaths in the two world wars was due to untreated bacterial infections because of a lack of antibiotics. Today antibiotics are so cheap that hundreds of tons of antibiotics are fed to livestock. (The easily available cheap antibiotics is causing its own problems. Lesson being that solutions create their own problems.)

The price of a traveling across the continental US within 6 hours was also $Infinite in 1940 (or anytime year before that.) No one had ever had traveled at 500 miles an hour at an altitude of 30,000 feet for most of human history. Now millions of people do that routinely every day.

Unimaginable Future

What humans can do today would have been unimaginable to those of the past centuries. This is the result of a universal human condition: that we cannot imagine very much. We cannot imagine anything that’s truly novel.

But wait, you say. We started this piece with a flying horse, didn’t we? Flying horses don’t exist and yet we can easily imagine a flying horse. So what gives?

The fact is that horses exist and so do wings, and we have seen winged creatures fly. Therefore flying horses don’t involve imagination as much as it involves synthesizing of bits already around.

The truly novel is unimaginable. We cannot imagine what kind of technologies will exist in the future. A caveman could not have imagined the kind of technologies we take for granted. Even Einstein could not have imagined what we have today.

At this point you may be wondering what all this has to do with the topic of climate change. I was coming to that.

Climate Change: The Hysteria

I find the whole issue of climate change fascinating. I marvel at all aspects of the phenomenon, not least of which is the global hysteria among a certain segment of the population. It represents a toxic mixture of politics, economics, science, ignorance, myopia, stupidity, fear, hubris, technology, power dynamics, racism, benevolence, malevolence and arrogance.

The colloquial definition of hysteria is “ungovernable emotional excess“. A hysterical person is best avoided until calmness descends (which usually happens) on him. Mass hysteria is harder to deal with. You cannot easily escape the effects of public hysteria whipped up by the mass media and other interested parties. Some people uncritically respond hysterically to messages of general doom and gloom. They amplify the noise which drowns out any signal that may be relevant to a reasoned understanding of the issue.

There must be a variety of reasons for people to feel concerned about impersonal matters that they are not personally responsible for and that they have little control over directly. One of those reasons is “virtue signalling.” In effect, their internal dialog proceeds thusly: “I am aware of a very serious issue that you are ignorant about and are oblivious to the danger it represents. I know and you don’t. I care and you don’t. I am more virtuous and better than you.”

One of the worst offenders in the climate change business (and it is a business, we must admit) is Al Gore. (I find it curious that he is a cousin of the late Gove Vidal, arguably one of the sanest modern Americans.) I concur with Charlie Munger’s assessment that Al Gore is an idiot. [Thanks to Rajan Parrikar for the link.]

We should remind ourselves that climate change is only the latest of a tradition of doom and gloom prophesy. Not too long ago, the gloomy predictions of doom was global cooling. The pendulum has swung the other way.

The Population Scare

One of my favorite Chicken Little “the sky is falling” doom-and-gloom stories is the population problem. Stanford University biology professor Paul Ehrlich stirred up quite a few people with prophesies of utter devastation in his best selling books “The Population Bomb” (1968) and “The Population Explosion” (1990.) He warned that hundreds of millions of people would starve to death because there was simply not enough food for the billions that would crowd the earth.

One of my favorite Chicken Little “the sky is falling” doom-and-gloom stories is the population problem. Stanford University biology professor Paul Ehrlich stirred up quite a few people with prophesies of utter devastation in his best selling books “The Population Bomb” (1968) and “The Population Explosion” (1990.) He warned that hundreds of millions of people would starve to death because there was simply not enough food for the billions that would crowd the earth.

I was persuaded by Prof Ehrlich’s argument. The naive easily fall prey to neo-Malthusian arguments. That was before I understood economics, specifically the role of technology, the power of human inventiveness, the magic of free markets, etc. But now I know better. I should mention also that it was before I read the brilliant Julian Simon (1932 – 1998), professor of business administration at the University of Maryland. I recommend his book “The Ultimate Resource” which you can read on the web here.

Julian Simon consistently argued what at first sight appears to be pure nonsense, but after proper reflection makes perfect sense. He said that that there are no natural resources. All resources are human creations. More about that some other time.

He famously won a bet that Ehrlich and he had.

Wanting to prove his theory that natural resources are not finite in a true sense, Julian challenged Ehrlich in 1980 to choose five commodities that he believed would become more scarce, and therefore more expensive, over a decade. Ten years later, the price of each metal had fallen. [Source]

For more on the Simon-Ehrlich bet, watch “Who Won the Bet of the Century?” [Thanks to Anup Nair for the link.]

Climate-change Hysteria is a Luxury Good

They used to call it “global warming” but then for nearly two decades the evidence for global warming was hard to come by, and so they changed the movement’s name to the more flexible and less specific “climate change.” Rise in temperature, fall in temperature, more hurricanes, fewer hurricanes, too much rain, too little rain, … everything can be attributed to climate change. The effects of climate change are so numerous that the phenomenon is non-falsifiable.

I note that only a segment of the human population has the luxury to indulge in the climate change hysteria. The billions, whose major concern is where their next meal is coming from, and who struggle with immediate and urgent matters of survival, cannot afford to worry about some dystopia cooked up in the fevered imagination of the comfortably off.

I wonder if there should be “Climate Change Rooms” like the fainting rooms that Victorian ladies used to retire to when afflicted by what was called female hysteria. Those climate change rooms would come in handy for the global elites when they are overcome with climate change hysteria exacerbated by jet lag with all their jetting around the globe in private jets worrying about CO2 emissions.

Leaving that aside, let’s cautiously wade ankle-deep into the murky climate change pool and examine what we find. Let’s note these basic fun facts.

Climate Change: Fun Facts

- The climate is changing. Big surprise? No. It has always changed and always will. The planet has gone through periods of warming and cooling, even when there were no humans around.

- Humans have an effect on the environment. Again, not a big surprise. Both for weal and woe, humans alter their surroundings. All living things do. It’s part of the deal.

- Humans emit carbon dioxide. All terrestrial animals generate CO2. On average, humans exhale around half a metric ton of CO2 per person per year. This is carbon-neutral because the food they eat removes the same amount of CO2 from the environment.

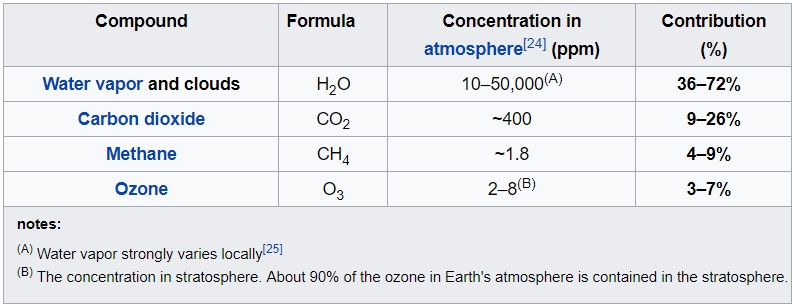

- CO2 is only one of the greenhouse gases. Here are some more:

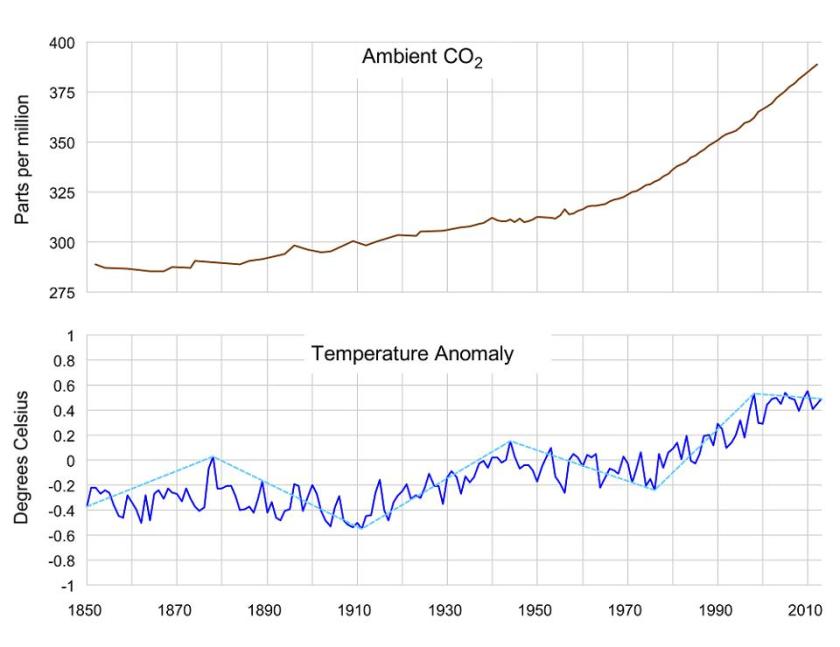

- There’s a positive relationship between atmospheric CO2 levels and average global temperature.Here’s an illustration of that fact (Source: Forbes.)

- In the above, note that the left hand side of the CO2 graph starts at 275 ppm of CO2. Also, that for over a decade the trend in the rising temperature has been flat while the CO2 levels have continually increased. This suggests that the response of global temperature to increasing atmospheric CO2 levels is likely to be less sensitive than previously thought.

- Also, note that it is not absolutely certain as to the causal link between CO2 and average global temperate. It could be that an increase in CO2 levels pushes up the temperature, or it could be that a rise in temperature causes an increase in atmospheric greenhouse gases.

- Human use of fossil fuels have contributed to the increase in atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases. Therefore, all else being equal, humans have had an effect on increasing the average global temperature.

- The mean sea level will rise with rising temperatures. By how much? By about one foot in a century. That’s about two centimeters per decade.

- The present climate models predict a rise of 3 degrees Celsius by the year 2100. Or about a third of a degree every decade.

It is important to remember that rising sea levels is manageable. People adjust to gradual changes. Richer people adjust better to changes. The entire land area of the world will not get submerged.

Temperature rise is not an unmitigated disaster. The present warmer areas will lose some agricultural productivity but the present colder areas will gain from longer growing seasons. There will be more heat deaths but there will be fewer deaths due to cold.

Higher CO2 levels mean agricultural productivity will rise. There will be more food for people.

Energy Use Powers Civilization

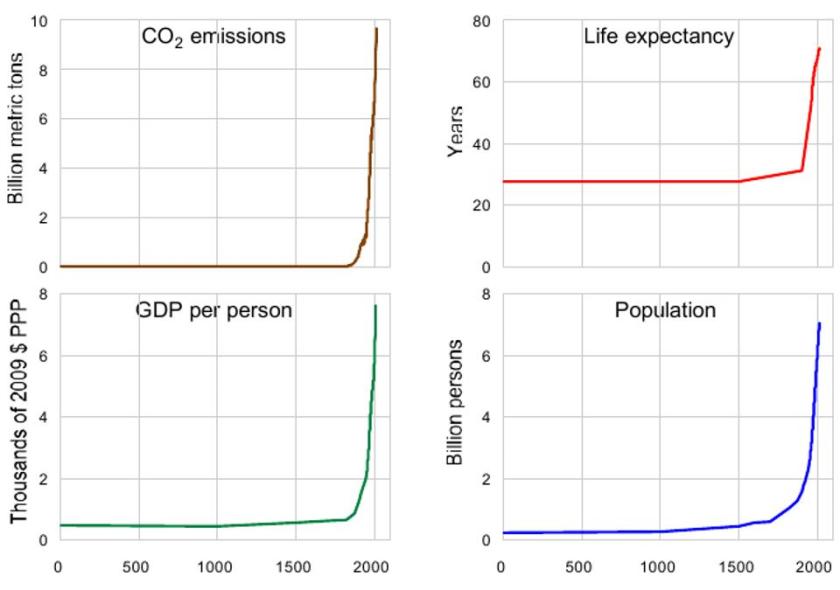

Here’s a neat set of graphs which illustrate one simple fact: humanity’s progress and the level of atmospheric CO2:

There is a correlation between CO2 emissions, GDP per person, life expectancy and human population numbers. Correlation does not imply causation but it suggests that there is a connection.

The story of civilization is the story of the progress humans made in the harnessing of energy. It starts with animal power. Wind and water power is also hundreds of years old. Then comes the use of coal, the first fossil fuel used. Then petroleum oil and natural gas.

With increasing use of fossil fuels came an increase in labor productivity — meaning we could produce more. That is what’s captured in the increasing GDP per person graph, and the increase in human population and increased life expectancy.

Expert Opinion Matters

There are lots of well-established facts on the matter of climate change. They include present and historical data. There are many climate models, and their projections depend on their assumptions about how the global climate responds to the various parameters in them.

Data are important. But data have to be interpreted properly and the implications of data varies with the interpretation. The jump from data (assuming that the data are unambiguous) to interpretation to likely scenario projection is not immune from major errors.

I am not qualified to judge the accuracy of those models. Therefore I would rely on the expert opinion of climate scientists. One often bandied about pseudo-fact is that “97% of climate scientists agree” on climate change. Alex Epstein has argued in Forbes that “‘97% of Climate Scientists Agree’ is 100% Wrong“.

If you dig a little deeper into the 97% claim, you find that it is just inflated rhetoric designed to mislead and misdirect. In a scientific survey paper by John Cook, the summary states, in part, “Cook et al. (2013) found that over 97 percent [of papers he surveyed] endorsed the view that the Earth is warming up and human emissions of greenhouse gases are the main cause.”

The “97% of papers surveyed” statement has been deliberately distorted to imply that 97% of all scientists (not just climate scientists) have reached consensus that there will be dangerous climate change if immediate steps are not taken to stop CO2 emissions. One former US president tweeted, “Ninety-seven percent of scientists agree: #climate change is real, man-made and dangerous.” The man has a reputation of playing fast and loose with facts.

I agree with Prof Steven F. Hayward of Pepperdine University. He said, “I think historians are likely to look back on the hysteria over climate change today the way we, today, look back on prohibition: as a comic misadventure that shows the harsh limits of political enthusiasm directed against basic facts of nature and society.” [Watch his video “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Global Warming”. Link below in the notes.]

Climate Change Not Dangerous

That’s a claim I make based on economic reasoning. We have to remember that no model predicts run-away catastrophic global warming. There is good reason to believe that the worst that is going to happen if we continue to do business as usual is a rise in average global temperature and a rise in the sea level. Those changes will happen at a glacial pace (if that’s the right metaphor here.) The good news is that even the worst predictions are not likely to happen, as I argue below.

There are more important and urgent things to worry about, and therefore deserve more of our attention and resources than climate change.

First, and foremost, a few billion people desperately need material prosperity. For that, the world needs more energy. There are a variety of sources: nuclear fission, coal, oil, natural gas, renewable like solar, wind, hydroelectric, biomass, etc. Ruling any of those out is not going to help the present generation of poor people.

The poor of the present should not be forced to shoulder the burden of ensuring a nicer world for the rich of the future. The poor of the present should not be made to suffer because some of the present rich believe that the world cannot bear the burden of many more people living materially richer lives.

Not a Climate Change Denier

I don’t believe that climate change does not matter at all. It does matter but it is not a yes-no question. It is a matter of trade-offs. The question is: how much does it matter relative to other things that deserve our attention?

Disease, hunger, armed conflict, the Religion of Peace — these global problems demand a systemic response today more than anything that is likely to be a problem in 100 years. How much will it cost to address those pressing problems of today, and how do those costs stack up against the cost of climate change mitigation efforts?

Many serious people have investigated the climate change issue. Bjorn Lomborg is one such. Consider his arguments, which you can find in books, articles, and easiest of all, on YouTube. [See linked video in the notes at the end of this piece.]

Researchers usually focus on the climate change problem without reference to the factors that I took some time to outline above:

- Technology will improve. In a few decades, if not in a few years, there will be technology to alter the climate anyway we like. Imagine a genetically modified bacteria that uses sunlight to convert atmospheric CO2 to produce energy. That would allow humans to set CO2 levels arbitrarily.

- People will have greater average and aggregate wealth. Therefore they would be better equipped to address any adverse climate conditions — including but not limited to global warming and sea level rise.

My argument that climate change does not matter as much as it is advertised to be is based on those two facts alone. We will know in a few years whether I am right or not.

It’s Economics, stupid

“It’s the economy, stupid” was the catch-phrase of Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 presidential campaign. A variation of that — it’s the economics, stupid — would serve us well.

In our world, change is not an optional extra. It comes as standard equipment, a non-negotiable feature. We live in the anthropocene, an epoch of significant human impact on the world. Climate change, both anthropogenic and natural, is to be expected. The question is how should humanity deal with climate change. Should drastic and dramatic action be taken? My answer is a definite no. I have presented pieces of the argument above and now it is time to wrap it up.

The historical case for discounting the doom & gloom stories of the climatistas is simple. One can come up with all sorts of scary scenarios which don’t hold any water the moment you throw technological change in the mix.

Climate Change and Horse Feces

Imagine 18th century London, England. The major form of transportation, for the minority rich who could afford it, was horse-drawn carriages. Naturally the streets had a lot of horse shit, which led to the problem of particulate pollution in the form of finely ground dried horse dung. The horse-dung alarmists would have had a field day warning of a day to come in 100 years when the streets would be six-feet deep in horse feces. The argument would have been simple: in the future, the population would increase, and a greater proportion of the population would have horse carriages, and so on. Technology in the form of horseless carriages precluded that dire outcome.

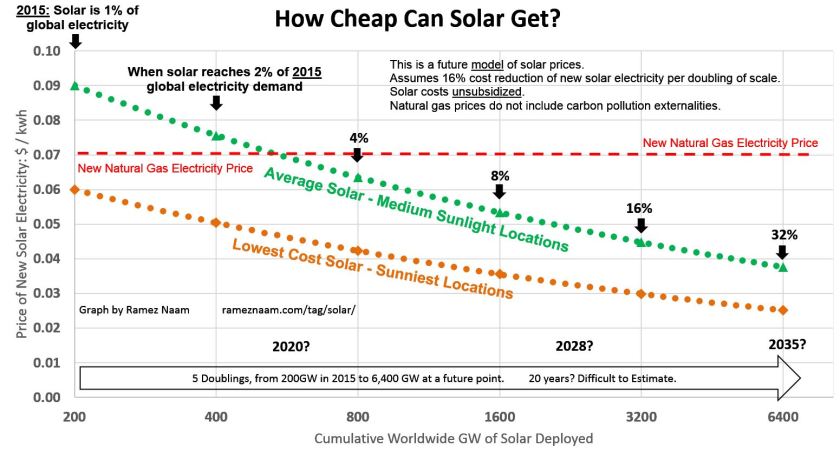

In our case too, the rapid development of technology will predictably change for future for the better. Two changes can be foreseen. First, the development of cheap, non-polluting, renewable sources of power. Solar technology is bound to become cheaper to the point that it would not make economic sense to keep using CO2 generating old technology. Here’s a graph projecting the future prices of solar-generated electricity (Source.):

Solar energy has one big drawback. The sun does not shine all the time in any location. Therefore, solar (and also wind-power) generated electricity has to be coupled with storage batteries for it to be truly competitive to the alternatives of fossil fuels (and nuclear.)

Therefore the second change that can be expected is that of cheap battery technology. A McKinsey report of June 2017 on battery storage notes:

Storage prices are dropping much faster than anyone expected, due to the growing market for consumer electronics and demand for electric vehicles (EVs). Major players in Asia, Europe, and the United States are all scaling up lithium-ion manufacturing to serve EV and other power applications. No surprise, then, that battery-pack costs are down to less than $230 per kilowatt-hour in 2016, compared with almost $1,000 per kilowatt-hour in 2010.

As I have noted above, technology makes all things cheaper. We can expect that storage costs and generating costs of non-fossil fuel energy will continue to fall, and eventually make it uneconomical to use fossil fuels. That’s why I say, it’s the economics, stupid.

Stone Age Ended. Fossil Fuel Age Will End too.

Economics has a term for it. It’s called “substitution.” Like things, technologies too become obsolete and get substituted. Stone tools get substituted for iron tools. As some have observed, the Stone Age did not end because the world ran out of stones. It ended because cheaper and better substitutes for stones were found. So also, fossil fuel use will end not because we run out of fossil fuels, nor because of government-mandated prohibitions against fossil fuels but because it would be cheaper to use renewable, clean energy sources.

The market, as we free-marketeers are wont to say, will figure out a solution to the problem of atmospheric CO2 that is reasonable, and for the most part unforeseeable. One part of the solution would be the cessation of CO2 producing energy generation; the other part will be technologies that remove atmospheric CO2 if there is sufficient justification for doing so.

Climate Change Hysteria Considered Dangerous

Climate change is on the card but catastrophic climate change only exists in the minds of some who have motives for their alarmist attitude. My position is that climate change is not the most urgent issue facing humanity today, and it will not be an issue in the future.

I believe that the catastrophic danger lies in people believing the hype and signing up to reduce the use of fossil fuels. Some of the measures being touted about is clearly insane, such as an 80% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2050. Assuming that no technological change takes place, and therefore no technological substitution of fuel sources, it would drag the world back about a century. But as I have briefly argued above, technological change is unavoidable and will make the whole issue of CO2 totally irrelevant.

Non-use or reduced use of fossil fuels will hurt those who are poor today, and make it much harder for them to gain some degree of material prosperity. Therefore, I think that developing countries like India and China should not be a signatory to any “climate change” agreement that puts limits on fossil fuel use and/or reductions in greenhouse gas emissions that go into effect any sooner than the year 2067 — that is 50 years from now.

Because by 2067, no climate change agreement made today would have any relevance. The world then would have moved away from CO2-generating fuels and would judge the present gang of climatistas as a bunch of motivated, ignorant, alarmist, self-serving busybodies.

A final point. I am an optimist. Human civilization is not likely to remain at the level it is today — 0.7 on the Kardashev scale. I think humanity will become a Type I civilization by 2050 — “the technological level of a civilization that can harness all the energy that falls on a planet from its parent star”. Not just in energy use, but practically all our present global ills, including the evils of monotheistic ideologies, will be gone long before Type I is achieved. As Carl Sagan observed, humanity is going through technological adolescence now. I don’t think that phase is going to last much longer than a few decades.

NOTES:

A couple of videos. First Bjorn Lomborg.

And Steven F Hayward.

Ah, been waiting for your take on this. Thank you for writing about it so lucidly. I loved reading the horse shit analogy. I wish I could share your optimism on the mentioned abominations going away before we become Type I and that too by 2050 … in our lifetime !?!? I have always thought the only way the monotheistic cults will disappear is if the incessant advent of technology results in us finding a way to incontrovertibly reveal minute details/events of heroes or so-called ‘prophets’ long in the past, so we know what’s myth and reality.

I will think through your points carefully and I hope to get back with some pertinent questions re. the real risk of anthropogenic climate change.

LikeLike

Atanu, that’s a great link on the Ladies Journal article with 100 year predictions from 1900. I marveled at it, but didn’t find it to be silly, it was pretty darned good! They over-estimated the human need for orderliness, and were absolutist in many predictions (e.g. mosquitoes will be eliminated; we’ve found no need to eliminate them but control them sufficiently in advanced countries). I found the live telecast around the world (prediction #10) and some of the medical predictions like imaging (prediction #27) to be right on the mark. Marie Curie’s work just about came to light at the turn of the century, so that must have enabled the medical prediction.

If at all, they’ve underestimated our progress across the board: space travel, sending a man to the moon and nuclear power being the biggest misses. That buttresses your larger point: even the smart among us are likely to underestimate / cannot really imagine what great things we end up doing even in 50 years.

LikeLike

Completely agree with your analysis regarding the climate change hysteria. Another hysteria going around is about the role of AI and technologies like 3D printing. While the new technologies you described in this blog and future new ones will make us more productive, I’m wondering if human population will adjust accordingly (since we need fewer hands). But how? Will people tend to have less babies because of increased life spans or more babies because they can afford more stuff due to productivity gains?

LikeLike

Future technologies will make humans more productive. That isn’t astonishing because that what has happened over the history of human civilization — people have figured out how to do things more productively.

What will be produced? That we cannot say for sure because if we could say, we would have already been producing that. Did anyone in the 17th CE know what that there would be personal transportation devices (cars) that would be commonplace? Could anyone in the 11th CE even imagine that common people would have the means to travel through the air at 500 miles per hour?

What will artificial intelligence and what it enables — robots that are immensely productive — mean for the economy? That it would mean cheaper material goods is certain. But how will that change the institutions that society relies on? As some others have recognized, it is not possible to predict precisely what emerges but the patterns are easily predictable. It would mean greater wealth on average and economic progress. The people of the future would enjoy lives that are as unimaginable for us as our lives would have been to those a couple of hundred years ago.

Will people have fewer babies? Most certainly. Fewer babies are the trend. For sure increasing life spans would act as a natural brake on the reproduction rate. Moreover, the babies that are born will be designed; parents would choose the characteristics of their children as easily as we choose the features of the cars we buy. I can envision an improvement in the quality of people — smarter, better looking, healthier, etc — as technology advances. I am certain that the trend would be better people. In about 100 years, humanity would look as different from us as we are different from the chimpanzees.

LikeLike

This may be of interest to the visitors here:

Response to a climate-change-denier

LikeLike

This may be of interest to the visitors here (such as Wake Up) who do not understand what they read:

Reading Comprehension in English

LikeLike