Mr Katju, who is a retired supreme court judge, provided his insights into “abolishing unemployment in India” on social media yesterday. According to him, Soviet Russia solved that problem by “raising the purchasing power of the masses, and thereby rapidly expanding the economy and consequently abolishing unemployment.”

Mr Katju, who is a retired supreme court judge, provided his insights into “abolishing unemployment in India” on social media yesterday. According to him, Soviet Russia solved that problem by “raising the purchasing power of the masses, and thereby rapidly expanding the economy and consequently abolishing unemployment.”

Mr Katju explains in subsequent comments how the scheme is supposed to work. It’s about reducing prices to increase “purchasing power”, he says. I don’t think he understands what prices or purchasing power means.

I have appended at the end of the post a few screen captures of Mr Katju’s submission to facebook and a couple of comments from his readers.

Mr Katju notes the steps the Soviet government took included the steady lowering of commodity prices, stepping up production, and the creation of jobs that abolished unemployment. He further notes that while the US was suffering the Great Depression of 1929, the Soviet economy was “rapidly expanding.” While not endorsing the Soviet method for India, he says that India should do something so “we can raise the purchasing power of the Indian masses and thereby rapidly expand the Indian economy, which is the only way of abolishing unemployment in India.”

He ends by writing, “The central point, and therefore the main problem before India, is how to raise the purchasing power of the masses? Do we follow the method of socialist countries, or some other method?”

Soviet ex-Economy

All statements to the effect that the socialist economy is still a going concern, are inoperative. It’s an ex-economy

That Mr Katju speaks approvingly of Soviet socialistic methods is rolling on the floor funny for a start. Why? Last time I checked (and that was over 25 years ago), the Soviet Union, like the Monty Python parrot, was no more.

“The Soviet Union has passed on. It has ceased to be. It’s expired and gone to meet its maker. It’s shuffled off this mortal coil. It’s run down the curtain and joined the bleedin’ choir invisible. Vis-a-vis the metabolic processes, it’s had its lot. All statements to the effect that the socialist economy is still a going concern, are inoperative. It’s an ex-economy.”

But seriously, the Soviet Union collapsed not because the people were stupid or that the huge empire did not have natural resources (it was immensely rich.) Its economic collapse was the result of idiotic policies made by people who had no understanding of reality.

Water flows downhill. Legislation cannot make it flow uphill.

Reality is unforgiving. Go against nature and prepare to be obliterated.

Water flows downhill. No amount of government-made legislation can make it flow uphill — not even some legislation that says we will gradually slow the downhill flow by 5-10% every 2 years or so, until over time water starts flowing uphill. Reducing prices 5-10% every 2 years or so, as Katju appears to approve of, leads to only one thing: shortages.

Here’s a quick reminder. At any specific price, there is a quantity that gets produced, and therefore is available for sale. The quantity produced goes up with higher prices; and the quantity goes down when the price goes down. That’s the supply side. On the demand side, the opposite happens: when the price goes down, the quantity demanded goes up; and when the price goes up, the quantity demanded goes down.

In undistorted markets, the price of a commodity is the price at which the quantity demanded is roughly equal to the quantity supplied. Let’s call it the equilibrium price.

Economists know that reducing prices by government edict is the quickest and surest way to destroy productive capacity.

If the government mandates a price lower than that equilibrium price, the quantity supplied goes down, and simultaneously, the quantity demanded goes up. Result: shortages. Prices higher than the equilibrium price, conversely, produce excess supply.

Economists may or may not know much about the economy. But there is one thing they absolutely know: that reducing prices by government edict is the quickest and surest way to destroy productive capacity. It is as close to a “law of nature” as you can get in the social sciences.

In any well-functioning economy — the kind that we presumably wish to have, one in which people produce stuff in adequate quantities, in which there are no shortages, in which people are employed in creating wealth that they consume and save — prices are not arbitrarily determined by the whim of some all-controlling authority. Prices are critically important and cannot be tampered with without dire consequences.

Prices emerge from the decentralized activities of all economic agents (the producers and consumers), and it helps coordinate their activities. Those prices are the only reliable signals that economic agents use to decide what they have to do next. Without the accurate signals, the economy stumbles along like a blindfolded person who has no idea of which way to proceed.

Employment is a means, not an end.

If there is any, the basic function of an economy is production of stuff that people value — the production of wealth. The basic function of an economy is not employment. Employment is merely the means for a person to earn an income so that it enables him to buy stuff to consume. Production matters because we want to consume. And employment is merely a means to consumption (via production.)

The confusion of means and ends is rampant — as is evident with the idiotic obsession with employment. We don’t need employment. We need production.

Uncle Milt had some advice

In the 1960s, Milton Friedman on a visit to India, was taken to some public works site. An exchange went something like this. “Why were the workers using hand-held shovels to move earth instead of using mechanical shovels?” he asked. He was told that mechanical shovels would not employ as many people. He replied, “Then why don’t they use spoons instead of shovels? A lot more people would get employed.”

Because production matters, productivity matters. If 10 people can produce 100 units of stuff, each person “earns” 10 units of stuff. That’s their productivity (10 units per person) and that is also their income. If you want the income to rise, you have to increase their productivity. If they can produce 200 units, each worker’s income is 20 units. That’s what “purchasing power” means.

Futzing around with prices does not help

Purchasing power depends on the amount produced, and has nothing to do with futzing around with prices. The only way to increase the purchasing power is to increase production. That’s not quantum mechanics. If by changing prices one could increase the purchasing power of people, it would be a wonderful thing. There would be no poverty in any country which had a government that had the power to change prices.

All dictatorial regimes have the power to dictate prices. And they too frequently do. They futz around with prices and wages. The predictable result is always and inevitably increased poverty. Why? Because when you fix prices, you essentially blindfold the producers, and that leads to lower production, not higher.

The sun also rises

Even the mere suggestion that perhaps if the prices were reduced in minor steps that it would lead to some better outcome is insane. It’s as insane as thinking that by changing the compass directions, the sun would start rising from a different point on the horizon. The sun rises where it does and based on where the sun rises, we get our compass directions, not the other way around. Only an idiot would think otherwise.

Some idiots think that fixing prices will bring down poverty, or unemployment, or some such idiocy.

It’s my misfortune that I saw the tweet pointing to Mr Katju’s musings. I wrote a tweet expressing the hope that Mr Katju’s grasp of matters legal was better than his grasp of basic economics.

.@keshavbedi Hope @mkatju 's grasp of matters legal is better than his grasp of basic economics, which is that of an average 7-year old's.

— Atanu Dey (@atanudey) May 20, 2016

Someone, who clearly disagreed with my tweet, pointed out, “Katju was a supreme court judge. Seriously, let that sink in.”

That’s an example of an appeal to authority logical fallacy: an authority thinks something, it must therefore be true. What’s worse is that the authority being claimed is not even in the same domain. One can have justified confidence in the authority of a neurosurgeon’s opinion on brain surgery but not on his opinion on how to run an auto company. This is worse than appeal to authority; it’s an appeal to the wrong authority.

[The strike-through text above is a correction because Mr Krishna Reddy G subsequently told me that he was being sarcastic.]

I did appreciate the fact that Mr Katju was a supreme court judge. And that frightened me. It is shocking that a supreme court judge has so little grasp of what is essentially basic common sense — or at least it should be common sense.

The basic ideas of economics should form a part of everybody’s cognitive toolkit — including that of supreme court judges. Because not having them causes immense avoidable harm to society, as we can easily ascertain when we look at what happened to the Soviet Union, and what’s happening to Venezuela.

Among those basic economic ideas are those of division of labor and specialization. By dividing tasks, we become more productive, individually and collectively. That means a farmer can focus on growing corn, and trade his corn for all the various other bits he needs from others who themselves focus on their own various specializations.

Specifically, I can spend my energies mainly understanding economics by reading dozens of great thinkers who have spent their entire lives specializing in economics. I have to read the ideas of Smith, Ricardo, Mills, Bastiat, Menger, Mises, Schumpeter, Kizner, Knight, Hayek, Buchanan, Simon, Friedman, Coase, . . . (and others that non-economists have probably never heard of) in dozens of books and ponder their insights so that I can understand a little better what the nature of the beast is. It takes all my time, leaving me to rely on others for the fruits of their labor for my survival.

And if I need legal opinions, I would go check with some learned judge or lawyer about that because I don’t know that stuff, and what’s more, I know that I don’t know.

But if I get into the business of dishing out uninformed legal opinions, it would not be pretty — it would be as disastrous as when a learned judge starts pontificating on how to cure the various economic ills of a large economy.

My main point is that one should know the limits of one’s understanding and never stray out of it, for there be dragons.

OK, here’s a screen shot of the original submission.

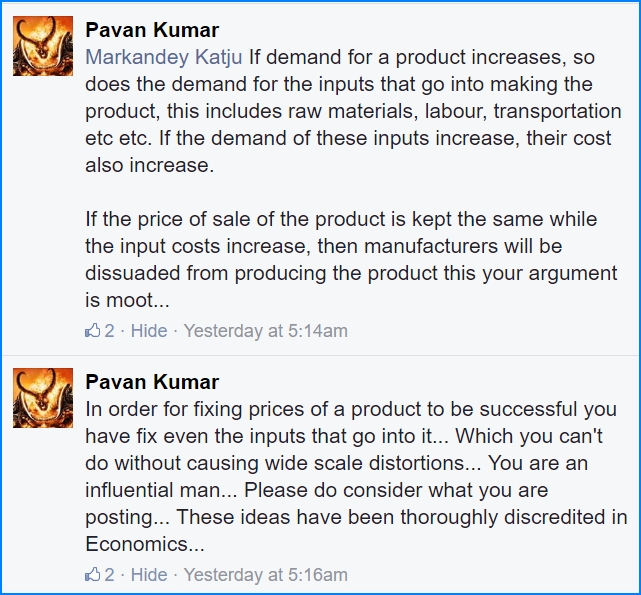

One commenter brings in some economic sense.

But you can see that there are lots of others who really don’t know what they are talking about and what’s worse, they don’t know that they don’t know — somewhat like Mr Katju.

The moral of the story: get some basic economics literacy before offering solutions to nearly intractable macroeconomic problems.

The solutions offered in the final screen shot are pretty useful for me. I am using them in my presentation to chartered accountancy students under the title “How to screw your economy” !

LikeLike

As Dr Thomas Sowell said – The first lesson of economics is scarcity: there is never enough of anything to fully satisfy all those who want it. The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics.

Wonder what the first rule of Judge K is.

LikeLike

Man you’re funny. As in you have a good sense of humour. I laughed so hard on the spoons for shovel anecdote and the river flowing upstream. Although I’m rather sceptical of economics as a formal science, I like your style. Good going.

LikeLike

Thank you, nirajshrivastava.

Economics is not a science. It does not deal with predictions. Physics is a science. Economics is a way of understanding how the world of humans functions. At the core is the idea that individuals are self-interested, reasoning beings. They act in their self-interest, where the self is defined broadly. In the case of a parent, that self — and therefore the self-interest — extends to the children. Humans reason and try to get the most that they can. They are not perfectly rational. But they are sufficiently rational in that they respond to the problems they face in ways that helps them.

Because the subject of study in economics is human beings, it is necessarily not a science in the sense that the physical sciences are. The primary reason is that humans behave strategically.

Here’s a bit from a previous post, Central Planners and Wooden Boards:

In my favourite Bruce Lee movie Enter the Dragon (which I have watched at least a dozen times) there’s a very telling scene. Just before a particular fight, Bruce Lee’s opponent, to demonstrate how awesomely tough he is, holds up a wooden board and with one swift punch smashes it to bits. Bruce Lee impassively looks him in the eye and calmly says, “Boards don’t hit back.”

People are different from things. Things are easy to understand and deal with. But people hit back. They behave strategically. They respond to stimulus and they respond to incentives. This is why economies are hard to understand and even harder to manage. But some people labor hard under the delusion that they can do things that are impossible. Tragic consequences of hubris — somewhat like technological hubris.

Technology’s marvelous ability to bring all sorts of amazing things to life (pun intended) frequently inspires hubris and consequent disasters. Science, in contrast, teaches humility because basic scientific advance more often than not sets boundaries to what is possible.

In any area of ignorance, the limits are not known and everything is possible. But with increasing knowledge of science, we begin to know and appreciate the limits. These limits are useful since it prevents people from attempting to do what is impossible. People had no reason to believe that there is an ultimate speed limit until Einstein came along and showed that there was. Thermodynamics tells us that it is pointless to try to invent a perpetual motion machine. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle imposed limits on how precisely you can know position and momentum.

There’s an analogue of this in the social sciences. In a sense, economics is the study of limits. The lesson a careful study of economics teaches is humility. One of the most fundamental lessons is that humans have bounded rationality and very limited ability to comprehend (leave alone direct) complex systems.

LikeLike